On line music notation: Noteflight

February 23, 2019 At the most recent Jazz Education Network (JEN) conference last month, some of us composer-arrangers spoke at length about Noteflight, an online music notation app and storefront. Similar in design and scope to the free, open-source MuseScore, Noteflight is owned by the publishing mega-corp Hal Leonard, purchased from a start-up in 2014. Noteflight is free to register and get using, so you can create and share scores that play back, and print. But to access some premium settings (like parts extraction) and to be able to sell music in Noteflight Marketplace, there’s a fee of $7.95 a month or $49.00 annually.

At the most recent Jazz Education Network (JEN) conference last month, some of us composer-arrangers spoke at length about Noteflight, an online music notation app and storefront. Similar in design and scope to the free, open-source MuseScore, Noteflight is owned by the publishing mega-corp Hal Leonard, purchased from a start-up in 2014. Noteflight is free to register and get using, so you can create and share scores that play back, and print. But to access some premium settings (like parts extraction) and to be able to sell music in Noteflight Marketplace, there’s a fee of $7.95 a month or $49.00 annually.For an advanced user like me, at first glance Noteflight wouldn’t be very attractive. My workflow has been pretty well established for years – er, decades – in desktop apps like Finale. I can sync with Dropbox if I need cloud accessibility, and I require fast, robust functionality, which is in 2019 is rarely available online to the same degree as a traditional desktop app would provide. However, as a jazz arranger, one aspect of Noteflight really caught my attention at the JEN conference.

Some Background

Hal Leonard runs Noteflight, and they also hold the copyrights for most popular music. For better or for worse, in the big-fish-eat-little-fish world of music publishing we now live in, HL has come out pretty much on top. For the last 20 years or so, one of the biggest effects this has had on the industry is HL has become a powerful gatekeeper for access to arranging licenses: if you want to arrange, say, a jazz standard, chances are very good that HL owns the publishing copyright to that song… so if you want to write an original arrangement of that song (and especially if you want to sell that arrangement), strictly speaking, you need to have approval from HL to do so, and make an agreement with them specifying how any royalities will be paid, etc. The copyrights for that song belong to someone else, in other words, and one can’t just appropriate it for their own uses and make money with it from, say, concert ticket sales. Or selling the sheet music (this is simplifying somewhat, but that’s the gist of the matter).

Hal Leonard runs Noteflight, and they also hold the copyrights for most popular music. For better or for worse, in the big-fish-eat-little-fish world of music publishing we now live in, HL has come out pretty much on top. For the last 20 years or so, one of the biggest effects this has had on the industry is HL has become a powerful gatekeeper for access to arranging licenses: if you want to arrange, say, a jazz standard, chances are very good that HL owns the publishing copyright to that song… so if you want to write an original arrangement of that song (and especially if you want to sell that arrangement), strictly speaking, you need to have approval from HL to do so, and make an agreement with them specifying how any royalities will be paid, etc. The copyrights for that song belong to someone else, in other words, and one can’t just appropriate it for their own uses and make money with it from, say, concert ticket sales. Or selling the sheet music (this is simplifying somewhat, but that’s the gist of the matter).And since HL is in business to sell their own, authorized arrangements of these songs, it’s often not in their interests to grant licenses to individuals or small publishers so they can release competing arrangements. HL’s own, in-house arrangers are on salary and make no royalties from the sale of their own arrangements as part of their contract (arrangers rarely make royalties from anything at all, if you didn’t already know that), and HL can sell those arrangements for years and years at a tidy profit. At one point, I contacted someone pretty high up at HL with an arrangement lots of people seemed to like – of a public domain tune! – with a strong live recording featuring a well-known soloist. The response was a quick dismissal: “We already have charts on that tune.”

This situation leaves many jazz arrangers in a dilemma. For most of us, we learned our craft writing charts on standards. I still focus on my original works, and work with some great publishers for those. But the songs of the Great American Songbook is mother’s milk for the arranger, and that vast body of classic tunes is the origin of our language. They’re the songs most familiar to the audiences we want to write for. We love them, and if you’re like me you have a closet-full (or hard drive-full) of swinging, creative, lovingly crafted arrangements. But most of those American Songbook songs are – for the time being – still under copyright, and only a trickle of them will come into the public domain during our lifetimes. So what can be done with all those fantastic standards we’ve arranged over the years?

We can’t submit them to smaller publishers. One head of a well-known publisher, one you have heard of and played their releases, told me they wouldn’t even look at charts on standards. I submitted two charts on pop tunes to a different publisher you’ve heard of a few years ago – charts that had been recorded on a commercial album – that let me know they would gladly accept them, and release them as soon as they got permissions. Going on three years later, those two charts are nowhere to be found in their catalog. They recently told me “we’re only granted a handful of licenses a year… we’ll keep on asking, though.”

We also can’t sell them ourselves, above-board. In the past… well, in the past, since the amount of money actually in question was so small, if you asked most arrangers directly, they would give you the chart themselves for a few bucks and a beer at the next gig. Writing jazz arrangements never was as solid an investment as, say, speculating in pork futures. But living here in 2019, the age of

We also can’t sell them ourselves, above-board. In the past… well, in the past, since the amount of money actually in question was so small, if you asked most arrangers directly, they would give you the chart themselves for a few bucks and a beer at the next gig. Writing jazz arrangements never was as solid an investment as, say, speculating in pork futures. But living here in 2019, the age of The bottom line is, there’s a tiny bit of money left on the bottom of the barrel for arrangers, and where those crumbs were left for us in the past, now those are starting to get scrapped up as well. So should we just delete/trash those arrangements, or keep them hidden in our basement, and tell our students not to write charts on standards, lest they entangle their young careers in legal proceedings?

If you can’t beat ’em….

While it’s tempting to cynically think of Hal Leonard’s Noteflight as another way to squeeze the last few bucks out of the market, for arrangers faced with the notion of burying some of their best work, Noteflight offers a legitimizing solution. One of the biggest selling points for Noteflight is that one can look up any piece of music on their database and see if HL owns the copyright – in most cases they do – and if they have it, and if it’s OK for arranging – in most cases it is – you can produce and distribute an arrangement through their Marketplace, no need for further approval, or even waiting. For arrangers, the upshot is that through this very streamlined process, you can sell “legitimate” arrangements of standards immediately. Well, now you have my attention. And this places Hal Leonard in a very unique (and powerful) position in the online publishing field. They have the legal means to vastly expand the publishing market to anyone with a computer and a little bit of music notation knowledge, and can monetize it. Is this the answer we’ve been looking for, like everything else these days, finding salvation in corporate online technology?

Test Case

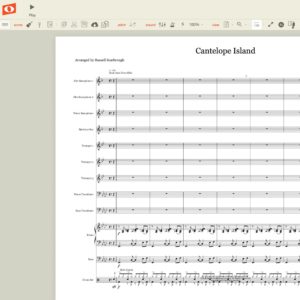

The chart on Noteflight’s web site, in case you’d like to follow along.

I decided to test this out, to see if it wasn’t too good to be true. I have a 12-piece big band that performs mostly soul-jazz arrangements of tunes from the 60’s and 70’s. For that group I have a chart on Herbie Hancock’s Cantaloupe Island, not too long or complicated, mostly a vehicle for grooving and letting anyone in the band blow over its three chords. I searched HL’s database on the Noteflight web site and found it was OK to arrange and distribute through the Marketplace. Double-checking, I found that some others had already made their small group charts of Cantaloupe Island available, so clearly this was a good choice for this experiment. If anything goes wrong, if there’s any fine print that ties this chart up, I haven’t lost much.

I decided to test this out, to see if it wasn’t too good to be true. I have a 12-piece big band that performs mostly soul-jazz arrangements of tunes from the 60’s and 70’s. For that group I have a chart on Herbie Hancock’s Cantaloupe Island, not too long or complicated, mostly a vehicle for grooving and letting anyone in the band blow over its three chords. I searched HL’s database on the Noteflight web site and found it was OK to arrange and distribute through the Marketplace. Double-checking, I found that some others had already made their small group charts of Cantaloupe Island available, so clearly this was a good choice for this experiment. If anything goes wrong, if there’s any fine print that ties this chart up, I haven’t lost much.But thankfully, one doesn’t necessarily need to input all that music through the interface. You can import music xml, so one can save a completed Finale file as xml and import it into Noteflight, which worked surprisingly well when I tried it with Cantaloupe Island. You still have to spend time tweaking the unanchored details from the import, of course, and you have to make parts in Noteflight (doesn’t import those, unfortunately), which is time-consuming, and something to consider if you have a long, complicated chart to import.

Incidentally, I should point out, like all online apps, Noteflight is very much a work-in-progress. Encouragingly, there does seem to be pretty solid online support, an active user community, and ongoing work in upgrading the software. This bodes well for the future of the platform, and is a big incentive for me to invest the time and energy in learning to use it well, and to help drive more development.

With the learning curve I was dealing with, and my OCD fussiness, it took about two hours to get the score to the point where I was willing to call it acceptable. Some issues I had to deal with: placement of text expressions is particularly clunky, it’s hard to select certain elements by clicking for some reason. The online interface seems to respond slowly to lots of minute adjustments done in rapid succession. Articulations are strangely limited: the lack of any jazz articulations was almost a show-stopper for the whole project. No falls or scoops. To indicate a simple fall, I reverted to taking an open-ended slur and re-shaping it (for each instrument) into a fall, which then reset itself to its original shape if I had to make further adjustments to anything else in the bar. If there was one essential, easy-to-implement upgrade I’d suggest to the Noteflight developers, proper jazz articulations would be it.

Noteflight also has an online playback feature, naturally. It sounds about like how Finale playback sounded in 1998. For me, that’s not critically important – robot playback is never going to give a decent reflection of an actual jazz performance, and I don’t expect anyone to stumble upon my arrangement browsing in the Marketplace and make an impulse buy based on what they hear through the playback feature. Fortunately, I have a good live recording of this chart to link to anyway. Meanwhile, the drum set layout is not really standard and not adjustable (I don’t put the closed hi-hat on top of the staff, do you?). But Noteflight is not meant to be the tool to make a proper demo.

At this point, I needed to become a “premium member” to extract parts (actually, you can get a 30-day free premium trial period). The Part Extraction feature is apparently new (introduced fall 2018), so I’m already on the bleeding edge of the technology here. Multimeasure rests have to be made manually. Drum charts, which are really a challenge to do right in Finale, are stomach-churning here. I don’t have woodwind doubles in my Cantaloupe Island chart, but I believe they’re basically impossible (no transposing staff styles) as things stand now. But after a couple more hours, much of which was learning-curve time spent figuring out how to get the text sizes and page margins to work properly, I got all my parts made.

The publishing part was actually pretty straightforward. Sign up for selling and provide direct-deposit information so you can collect your 10% commission from sales (which is, eh, if you’re already paying to play), and you’re good to go. In your ready-for-prime-time chart, hit “sell”. You leave the credits, title, and copyright text off of the score, and Noteflight fills that in automatically when you select the title from their database

(which I had already checked before I did anything, naturally). So now the title page has the composer(s) name, you listed as the arranger, and all the proper copyright citations at the bottom. You select the categories to market this chart (jazz, intermediate level, “small group” I guess, since big band or jazz ensemble isn’t an option, despite it being a Marketplace category), and you decide on a price – Noteflight establishes a minimum cost based on size. You can give it a little write-up, make it look snazzy with an cover image, and voilà, you’ve published a legitimate arrangement of a standard tune.

Conclusions

Overall, considering I was learning the interface, it wasn’t too bad. It didn’t take forever and most of the “how do I…” questions I had along the way were easily answered by googling their website with the inquiry. With a chart already complete in Finale, I got 95% of the work done by simply importing the music xml into Noteflight. My next project will be to use this first one as a template to streamline the importation workflow. If I could get the whole import-to-publish process down to a couple of hours, that would make Noteflight a really valuable tool for me.

Noteflight does have a long way to go in being an app that can produce really professional-looking charts. Even the pieces from their own catalog, sitting side-by-side in Noteflight Marketplace with those by regular users, don’t look that great, and really pale in comparison with their traditionally-produced counterparts. There is a handwritten “jazz” font option that I decided against using after seeing what it made a few charts by prominent HL arrangers look like. I know some arrangers who will not even consider Noteflight based on the non-professional look of the charts, and I don’t blame them. For myself, it’s a question of priorities, and it’s not a slam dunk in favor of Noteflight when I’m weighing the pros and cons.

And sales potential is not a major “pro” for Noteflight. I don’t know if I’ll sell 10 copies of my chart in a year (the minimum I’d need to move to break even, considering the $49 annual fee). Even a basic function like “sharing” a score, so you can drive business to the site, is weirdly hard to do and very limited (I know, right?). But sales potential aside, that’s not the reason I conducted this experiment.

Like most jazz arrangers, I have a lot of charts on standards. For, pro groups, for students, for pedagogical purposes, for jazz musicians who wanted a solo vehicle. Right now, those charts are sitting around; I know they’re good, but I can’t even submit them to a publisher to try to make a trickle of money back, to get the charts played somewhere, and to get a publishing credit on my CV. Because of industry standards and copyright laws jerry-rigged to benefit mostly copyright holders of music that generates money on an enormous scale, I can’t legitimately use any of the the arrangements I’ve written even in settings that generate little-to-no money at all, but are nevertheless the very settings where my reputation and credentials as a writer are best established. I’ve got mad court skills, but the hoops are off limits.

So this Cantaloupe Island chart is an experiment – to see if the set-up is even viable (it is, albeit with compromises), to see if I can make a trickle of money back (maybe, we’ll see), and to get the chart out there (maybe, we’ll see). And above all, to have an arrangement that is bulletproof legally (seems so, yes). Now if a buddy of mine, a prominent jazz soloist, wants a chart on a standard, I can say “yes” and collect a commission on that arrangement that won’t get me in trouble down the line when he performs it everywhere… Hal got paid, I got my permission.

That’s my thinking on it. Noteflight can still be made a lot better, but it does seem like they are pretty serious about supporting it. It could wind up being that I’ll abandon it later if it becomes more trouble than it’s worth. I’m not pleased with the increasingly litigation-minded direction the industry is going lately, especially as it targets the little guy so much. I understand the legitimate need for copyright protection, but here in the 21st century, it mostly serves to protect large entities from smaller ones, and not the other way around as it was intended. Even if major reform were to happen in the future, it won’t happen quickly, and us little guys need to be able to use what tools are made available as we can. HL could, if they put a lot of energy and thought into developing Noteflight as a platform that could serve the needs of professionals like myself, its conceivable that this could be the direction to the best of both worlds, where content producers actually get paid and can manage their own works, and HL could make plenty of cash being the platform where all that freedom and commerce reside all at once (Finale and Dorico developers, are you paying attention?). For now, at least I have the proof-of-concept of an imperfect method to produce arrangements that I can play/sell anywhere, above board, where before I couldn’t. Next up, Love Theme from “Herbie”.

That’s my thinking on it. Noteflight can still be made a lot better, but it does seem like they are pretty serious about supporting it. It could wind up being that I’ll abandon it later if it becomes more trouble than it’s worth. I’m not pleased with the increasingly litigation-minded direction the industry is going lately, especially as it targets the little guy so much. I understand the legitimate need for copyright protection, but here in the 21st century, it mostly serves to protect large entities from smaller ones, and not the other way around as it was intended. Even if major reform were to happen in the future, it won’t happen quickly, and us little guys need to be able to use what tools are made available as we can. HL could, if they put a lot of energy and thought into developing Noteflight as a platform that could serve the needs of professionals like myself, its conceivable that this could be the direction to the best of both worlds, where content producers actually get paid and can manage their own works, and HL could make plenty of cash being the platform where all that freedom and commerce reside all at once (Finale and Dorico developers, are you paying attention?). For now, at least I have the proof-of-concept of an imperfect method to produce arrangements that I can play/sell anywhere, above board, where before I couldn’t. Next up, Love Theme from “Herbie”.